The strategy behind conspiracy theories

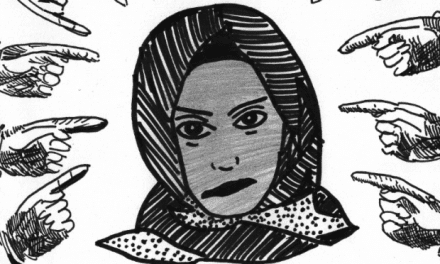

Conspiracy Theories Are for Underdogs

By ADRIENNE LAFRANCE

Donald Trump’s recent tweet about long-secret JFK files is a way for the president to try to reclaim a status that has repeatedly helped him.

One of the stranger aspects of having a conspiracy theorist in the Oval Office is that it goes against the way conspiracy theorizing usually works.

Conspiracy theories are a way to stand up, through disbelief, against the powerful. Those who spread conspiracy theories in earnest are, whether they mean to or not, partaking in an act of defiance against established institutions as much as they are questioning accepted truths. Usually, then, a refusal to believe the widely accepted explanation of how something happened originates from outside of official channels like government. A president might be the one accused of the conspiracy; rarely is he the one spreading rumors.

Donald Trump is not like other presidents.

Trump is powerful, yes. And he has been for decades. Before he was president he was a wealthy television star and real-estate developer. He was long famous for being famous, a fixture in the New York City tabloids since the 1980s. Yet he has all the while gravitated toward tall tales and hoaxes. Today he is the president who falsely cries “fake news” about the legitimate information he dislikes. He is also the most famous champion of Birtherism, the lie that Barack Obama was born outside of the United States. And he is a performer who has, for decades, relished occupying the public space between real and make-believe, whether as a game-show host on reality television or in the pro-wrestling cameos he made.

Trump’s involvement in all this isn’t universally—or even mostly—malicious, but looking at the president’s involvement in make-believe over four decades does reveal a spectrum of truth-bending. Far on one side is the playful end. That’s where you’ll find Trump doing scripted wrestling stunts and strutting around on The Apprentice. Opposite that is the manipulative and maybe even authoritarian side of the spectrum—where he’s peddled Birtherism and made increasingly disturbing attacks on the free press.

The curious thing about all this is the extent to which these various performances of alternate reality converge. In 2017, Trump’s previous pro-wrestling playacting dovetails neatly, and in gif form, with an attack on the Fourth Estate. And his tabloid-fueled, campaign-trail conspiracies about the JFK assassination—he suggested the father of a political opponent, Ted Cruz, was somehow involved—are the backdrop against which the public must attempt to contextualize a presidential decision about open records.

“Subject to the receipt of further information,” Trump tweeted Saturday morning, “I will be allowing, as President, the long blocked and classified JFK FILES to be opened.”

Trump’s announcement came a day after his longtime confidant Roger Stone went on Infowars, a radio show and website known for spreading conspiracy theories, and announced that Trump would not block the release of the documents, which are set to be issued by the National Archives in the coming days. Earlier that day, Politico Magazine had published an in-depth piece saying that Trump would likely block the release of the files.

Here’s the thing that happens, apparently, when a conspiracy theorist becomes president of the United States: The lines between decision and reaction blur. The American people are accustomed to public officials spinning their way through public office. No president has been truly forthcoming with the electorate. Many have misled the American people.

Yet Trump isn’t just indifferent to truth, as any neutral party can see; and he isn’t solely set on deceiving the public, despite what many of his critics insist. Donald Trump isn’t even first and foremost a performer.

He’s a pretender. And he has a preternatural sense for what people want him to be.

So when Donald Trump suggests he will help the public access long-secret JFK files in the name of transparency, he’s doing it with the same talent for identifying the kinds of stories that captivate people that he’s leaned on his entire career. (Those who have studied the JFK assassination closely are mixed on the potential significance of these files. “I’ve always thought that the release of these documents is going to be something like what happened on New Year’s Eve 2000,” Josiah Thompson, the author of Six Seconds in Dallas: A Micro-Study of the Kennedy Assassination, told me on Saturday. “A great big zero of happening!”)

Regardless of the files, though, Trump’s attention to them is a window into how he wants to be seen. In one dashed-off tweet, Trump positions himself as doing something noble—advocating for transparency, against the warnings of the intelligence community—while feeding at least two major conspiracies. One, that the press is “the enemy of the American people” working in cahoots with the deep state, and, two, by lending credibility to the idea that the official story of JFK’s assassination is indeed suspect.

“The best conspiracy theories have all the trappings of a classic underdog story,” wrote Rob Brotherton in his book, Suspicious Minds. “We want to see top dogs taken down a peg; we want the downtrodden underdog to triumph. And when it comes to conspiracy theories, unfair disadvantage is par for the course.”

The president of the United States is not an underdog. But Donald Trump has repeatedly leveraged a perceived underdog status into success—his comeback from bankruptcy in the 1990s and, more recently, his establishment-rocking presidential victory last year. Trump knows how well the underdog narrative has served him. And he knows exactly how conspiracy theories grab people. Spreading Birtherism was largely an attention campaign, one that helped establish a base of future voters who would eventually help elect him.

“Trump has built a coalition of conspiracy minded constituencies,” said Joseph Uscinski, a political science professor at the University of Miami and the co-author of American Conspiracy Theories. “Trump had no political experience, and he therefore had to justify his candidacy by appealing to conspiracy theories that impugned the establishment. Trump appealed to people who had conspiracy mindsets and who would normally be disinclined to vote, but Trump used conspiracy theories to motivate them.”

“Now, appealing to JFK conspiracy theories is a great idea for him,” Uscinski added, “because recent polls show that 60 percent of Americans believe in one form of JFK conspiracy or another.”

Trump’s focus on JFK comes, too, at a moment when it would serve the president to have the American people talk about anything other than his false claims about comforting grieving military families—and subsequent scramble to prove them. Trump certainly is not the underdog in that scandal.

“You need to be at a disadvantage, and your disadvantage needs to be unfair—due either to lack of resources or to the malicious actions of an aggressive opponent,” Brotherton writes of true underdogs in his book. “When we feel like somebody’s disadvantage is self-imposed—when they have all the resources to succeed and still fail regardless—we dislike them even more than a simple loser.”