By Katie Lange, DoD News, Defense Media Activity

When World War I ended, new countries were born and borders were redrawn in the Middle East. But those changes were marked with missteps that have led to many of the conflicts that have made it one of the most volatile regions in the world.

If you’re not sure why, here’s the basic gist.

The 1916-1918 Arab Revolt was often carried out by mounted Arab tribesmen, who knew the land intimately and were excellent marksmen. Library of Congress photo

The Middle East’s Role in WWI

The British, French and Russians had been jockeying for position over the declining Ottoman Empire for decades before World War I. But as the war unfolded, Germany’s spreading influence in the region brought concern from all parties. Great Britain wanted to protect its interests in the region – mainly oil and mobility via the Suez Canal – so Britain and its most important colony, India, sent troops to Bahrain. On Nov. 5, 1914, France and Britain declared war on the Ottoman Empire. The fight eventually moved east.

Organization Before the War

A map of the Middle East circa 1914.

There were three main components to the Middle East: the Ottoman Empire, Persia and Arabia.

During World War I, the centuries-old Ottoman Empiremostly encompassed the areas around Turkey, Mesopotamia, Syria and Palestine (Israel hadn’t been created yet). Armenia was also part of the empire.

Persia (modern-day Iran) was divided into three spheres of influence before the war: Russian-controlled, British-controlled, and a neutral zone. During the war it became a battleground for Russian, Turkish and British troops.

Arabia: This encompassed most of modern-day Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, Yemen and the United Arab Emirates. Parts of it were fought over by the Ottoman Empire for a century prior to the war, when power had gone back and forth, but the region remained relatively autonomous during World War I.

What Changed:

During the war, Arab rebels who wanted to be free from the Ottoman Empire asked the British for help. The British supported that request, with the help of France. When the war ended, the two European powers implemented a mandate system in the Treaty of Versailles that split up the former empire’s countries – much to the chagrin of those who lived there.

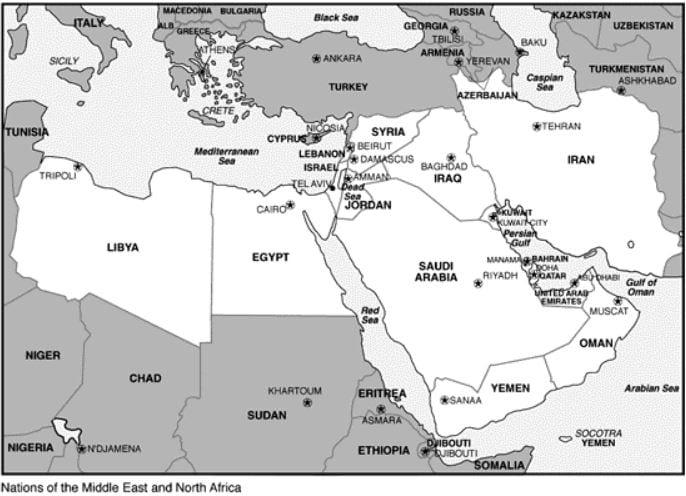

A current-day map of the Middle East.

Turkey, an independent republic at that point, became the successor state to the Ottoman Empire. It’s still the biggest and most powerful country in the region.

Lebanon was created as a state separate from Syria, which had seen Lebanon as part of its own territory for years. These were put under French rule and stayed that way until after World War II.

Mesopotamia (Iraq) had been made up of three former Turkish provinces – Mosul in the north (known as Kurdistan), Basra in the south, and Baghdad in the middle. After the war, they were united as one country under British colonial rule.

Palestine was put under British control and divided into two countries, with the western portion of it becoming Trans-Jordan (later, just Jordan).

Georgia and Armenia (northeast of Turkey) were given international recognition.

Persia: Since Russia had problems of its own (namely, civil war), Britain became the dominant force.

Arabia: In 1932, many of the region’s kingdoms and dependencies were combined into one, called Saudi Arabia. Yemen, Oman, Muscat and the states that would later make up the UAE remained independent.

The Discord that Followed:

The Arabian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in early 1919 included King Faisal (front, center) and Lawrence of Arabia (third from right). National Archives photo.

Iraq:

When Iraq was put under British rule after the war, three missteps led to conflict in the region that continues today:

- British leaders didn’t understand Iraq’s political or social issues and underestimated the popularity of the Arab nationalist movement (which was opposed to British rule).

- Iraq’s provinces were each ruled by tribes and sheiks and had their own ethnic, cultural and religious identity. They weren’t used to a centralized government, which now included the voices and protections of minorities like Jews and Christians, so discord erupted from the start. A rebellion in 1920 was quelled just in time for the following:

- The 1921 Cairo Conference.

- Agreements made at the conference drastically reduced British troop levels in a region that had little civil order and governmental oversite.

- The British also scrapped their promise to create an independent Kurdistan in Iraq’s north. To this day, Kurds in Turkey and elsewhere continue to defend their desire to become an autonomous region.

- The conference led to the next major point:

- The appointment of Faisal as king.

- At the conference, Faisal Bin Al Hussein Bin Ali EI-Hashemi – Faisal, for short – was installed as Iraq’s king since he was pivotal in the success of the Arab revolt against the Ottomans. But as ruler, he rejected British control and wanted to form a single national identity, despite the aforementioned tribes, religions and ethnic groups. Since then, mostly Sunni Arabs have had political control over land that was largely populated by Kurds and Shiites, and each group’s grievances have brought about violent confrontations.

Britain’s division of the mandated area.

Palestine/Jordan:

The Cairo Conference’s decision to install Faisal as king in Iraq also deeply affected Palestine and Jordan. Faisal’s brother, Abdullah, had been trying to regain Syrian independence from the French. But the British didn’t want to cause conflict with France, so it threatened Faisal, telling him he wouldn’t get to rule Iraq if Abdullah attacked Syria. To appease Abdullah, the British created Trans-Jordan from Palestinian land and made Abdullah its king. This split set the foundation for the Arab-Israeli conflict we see today, since it split in half the land that would be considered for a future Jewish national homeland.

Persia:

A lot went on in this region during the 20th century. Here are some of the main takeaways.

The Anglo-Persian Agreement of 1919 that was formed after World War I would have given Persia British money and advisors in exchange for oil access. But that was rejected by the Iranian Parliament in 1921.

Iran’s king, Ahmad Shah Qajar, was removed from power in 1925 by the parliament after his position was weakened in a military coup. Reza Pahlavi, a former military officer, was named the new king and, in 1935, renamed the nation Iran. He was deposed in 1941 following an invasion by Soviet, British and other commonwealth forces looking to secure oil reserves from possible German seizure. His son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, then became king (shah, as they call it).

U.S. President Gerald Ford and the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, look at charts during a state visit. Photo by David Hume Kennerly, May 1975, courtesy of Gerald Ford Library

Unrest due to corruption and the shah’s efforts to westernize the country finally bubbled over in 1979, and the shah was forced to leave Iran. The Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who had previously been exiled, returned to become the country’s supreme spiritual leader, and he made Iran a theocracy. Iranian revolutionaries, angered by American interests and political dealings in their country, also stormed the U.S. Embassy, accusing the U.S. of harboring the exiled shah, who had relied on the U.S. to stay in power. Hostages were taken, ties were severed, and thus began the lack of diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Iran that continue to this day.