Following eight years of tough austerity due to the economic crisis that hit the country, Greece is finally ready to return to normal. This is according to statements made by economic experts and politicians in Greece, as well as other Europeans and the heads of international financial organisations.

But while the economy remains a ‘hot’ topic and scores of analyses about the reasons for the crisis and the infrastructure changes have been discussed, the impact of the crisis on Greek politics remains largely untouched.

It is true the economic crisis in Greece has been catastrophic – dramatically changing the life of more than the half of the country’s 11m population. One of the biggest and most visible effects was a mass unemployment that led to acute pauperisation. This ‘national catastrophe’ further resulted in a historical overthrow of Greece’s traditional political parties and in the advent of new political players.

In the latest crisis, Greece’s political parties also felt the consequences of the crisis. In short, the traditional by-party system that led the country since the end of the 19th century was pushed into a transformation process.

Who can bring about change?

In Athens, a struggle is currently underway between the ruling Syriza party and the parties of the opposition. It’s a struggle over which side has more merit for the administration of the crisis and which can better manage a free-of-foreign-control Greece.

The merit of the real reforms and changes is exclusively that of the centre-left. And, the actual centre-left in the Greek political system is the once-radical Syriza party and its coalition government.

Why?

Throughout the history of Greece, in turbulent times, it has always been the centre-left that found solutions and helped the country to move forward. From the Asia Minor refugee crisis to the fight against the Communist party in 1930s, as well as the radical social change of the 1920s and 1930s, and from the defence of the liberated Greece by the Communists in 1944 and again the victory against the Communist-led Civil War until the deep social reforms of Andreas Papandreou in 1980s, the mark of the centre-left has always been well distinguishable.

This is because the centre-left has always had the mechanisms and the populist-inspired rhetoric to attract the Greek electorate. In addition, it has always been able to impose unpopular measures by ensuring the trade unions’ active or passive support.

Greece’s centre-left was, and still is, the party of the national industry and under its governing a non-official ‘class war cease fire’ was reached.

A by-party system tradition

Greece’s political system is characterised by bipartisanship, even though many times this by-party system has not been perfect. Overall, during periods of relative calm, Greece’s political spectrum has been dominated by two big parties. Even though smaller parties existed, these enjoyed only partial influence.

What is important is that, firstly, there was an alternation of power between the two biggest parties, and secondly, that those parties formed the trunk of the government. The two fronts were clearly distinguishable as being conservative and a progressive. Or, using today’s political terminology: centre-right and centre-left.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, two main political figures with their respective political parties dominated the scene. One was Charilaos Trikoupis in the progressive and industry-oriented camp. The other was Theodoros Deligiannis in the conservative, nationalist and pro-rural camp.

The Liberal Party of Eleftherios Venizelos and the Popular Party (the first representing the political centre and the latter a conservative and pro-Monarchy party) during the period between the two wars, the National Radical Union (conservative) and the Union of the Centre in the 1950s and 1960s and, after 1974 the conservative New Democracy and the populist Pasok, ensured the success of bipartisanship in Greece.

Each time, there was a ‘national catastrophe’ that heralded the political disappearance or isolation of the previous strong parties and the birth of new ones.

Such periods were: 1909-1922 (which started with a military revolt, the Balkan Wars, World War One and the drama of the Greek population in Asia Minor), 1936-1951 (marked by the dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas, World War Two, the German occupation of Greece and the bloody Civil War) and 1967-1974 (when the country fell under a military dictatorship).

In our time, the destruction of the Greek economy since 2010 had the characteristics of a catastrophe.

The crisis of the political world

The parties that dominated politics between 1974 and 2010 crashed under the austerity measures imposed by Greece’s international lenders. The electorate became disoriented and searched for alternative political proposals.

Pasok was the party that ruled for the longest time since 1981, winning the elections with 48% of the vote. In the January 2015 election, Pasok was defeated, winning a tiny 4.7% of the vote.

The conservative New Democracy party, which played an important role in the country’s European future during the 1970s, also suffered big losses. It saw its power in parliament severely reduced from 129 seats (2012) to 76 seats (2015).

But there is more to the story. New Democracy was practically split. The conservative, nationalist and neo-liberal tendencies control the party today. The traditional centrist tendency – represented by the followers of Konstantinos Karamanlis – offered a critical and passive support to the Syriza-led government. In fact, the president of the Republic, elected in 2015, was a prominent member of this tendency. Another part of New Democracy’s membership formed the Independent Greeks – a nationalist party, which is a minor partner in the Syriza government.

There are also new political parties that have emerged, such as the neo-Nazi Golden Down, the nationalist Independent Greeks and the centrist To Potami (The River).

The traditional by-party system collapsed. As such, a refreshing of the political powers in the centre-right and the centre-left was urgently needed.

The Syriza mutation

Among all the parties – old and new, the most successful has been Syriza. In origin, it was a bizarre mix of far-left groups (neo-Stalinists, Trotskyists and Maoists), Eurocommunists, ex-Communist Party members and former Pasok members.

Syriza emerged as a leftist party, similar to the other leftist parties that emerged in Europe, such as the Italian Rifondazione Comunista. But the new political environment provoked by the crisis pushed the party towards the political vacuum left by Pasok’s collapse.

The affluence of centrist elements and especially of many former Pasok unionists, since 2010, facilitated the mutation into a centre-left party.

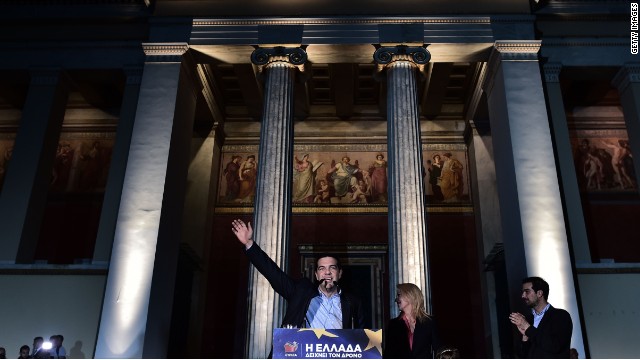

In fact, since 2010, Syriza has been sprinting towards the centre-left. Its political rhetoric was based on a vague use of the term ‘Left’ and on slogans based on ethics. To some extent Pasok’s political rhetoric under Andreas Papandreou in 1981 was much more radical. Papandreou promised Socialism once in power. Syriza never promised this, and during its 2015 electoral campaign the flags donning the hammer and the sickle disappeared from its public gatherings. A Greece free from the control of the IMF and the Eurogroup was the party’s main slogan.

Once in government, Syriza’s leadership worked hard to show a moderate, rather centre-left image and criticised the extreme radicalisation of the party’s leftist current.

After its honeymoon period in office and some rather pleasing actions undertaken by several of its ministers, Syriza relieved itself of its leftist elements and won a clear electoral victory in September 2015 snap election.

On the European political scene, Syriza seems to feel more comfortable with the Social Democrat leaders than with the traditional Leftists. In the European Parliament, the president of the SDs, Gianni Pittella, was a privileged interlocutor while the party of PM Alexis Tsipras is still a key member of the GUE/NGL Group.

This mutation was noticed by few. This is because Greek society was imprisoned by two main narratives. One came from Syriza itself. It loudly advertised its Leftist origins and called for a ‘first time governing Left’. The Leftist electorate, which represents a non-negligible part of the national electorate, was convinced. The other narrative was offered by the New Democracy party and to some extent by Pasok. According to them, Syriza was a covert communist movement that aimed to transform Greece into a country of the likes of Venezuela, Cuba and North Korea. Unfortunately, centre-right and Pasok politicians spent a lot of time trying to convince Greeks that Tsipras was a nouveau Castro or Maduro in the making.

The results of the next general election (according to the government the election will be held next year) will prove if the ‘catastrophe’ is over. If the electoral campaign will be polarised between Syriza and New Democracy, isolating the Movement of Change (the Pasok transformation) and if smaller parties like the Independent Greeks or the Union of Centrists are kept out of parliament, this will be a clear sign the country has returned to normality.