By Gary Ashton, Investopedia

This week Greece returned to the international bond market for the first time in three years with a 3 billion euro denominated bond that matures in 2022 yielding less than 5%. This is a remarkable comeback for a country that defaulted on its obligations twice in 2012 and still has a deeply distressed credit rating.

This new bond issue is important for debt investors because it signals two important things. First, it signals that investors are prepared to put the 2011 Eurozone crisis behind them and step in to buy new Greek debt. Secondly, it signals that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailouts of the Greek economy worked as intended to shore up investor confidence. It also demonstrates how bond investors are hungry for yield in this low global interest rate environment and are willing to buy bonds issued by riskier borrowers.

Why Are Yields So Low?

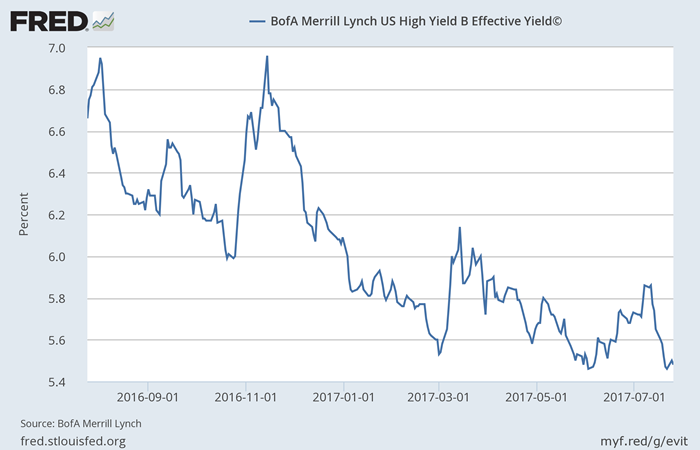

What is somewhat surprising is how low the yield is on this new bond. Various media reports say the yield is around 4.6%. Given the country’s still relatively risky credit ratings, this yield seems low. Greece is rated ‘Caa2’ at Moody’s and “B-” at Standard and Poor’s. Even giving Greece the benefit of the doubt and using the higher credit rating of “B-,” data from the St. Louis Fed shows that the effective yield on single B rated issues is currently around 5.5% (see chart), which is nearly 1% higher than Greece.

Part of the reason Greek debt does not yield more is because of how investor’s view the country’s relationship with the rest of the Eurozone and Germany in particular. Greece was not expelled from the block during the depths of the 2011 crisis (a concept termed Grexit). Instead money was poured into the Greek economy and banking system. It is because of this backing that yields on the country’s new debt do not completely match the country’s credit ratings.

The Bottom Line

Greece’s re-entry to the bond market this week is a positive step, but the country still needs to undergo important structural reform to improve the productivity of its economy and get its overall debt ratios more in line with other Eurozone countries. Failure to build on this positive momentum could limit the country’s ability to borrow again in the near term.