Many of the scholars engaged in creating Turkey’s early constitutions came from Mulkiye. The legislators tasked with building the young republic were able to do so in part because, even if their political backgrounds differed, they shared some of the same republican values. Foreign ministers, governors and ambassadors often came from Mulkiye, much as French politicians commonly come out of Sciences Po. Uzgel told me that it was generally known that you were less likely to attain a position at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs unless you had a degree from Mulkiye.

It was at Mulkiye, in part, that the foundations of Turkey’s foreign policy were established. In reaction to devastating wartime experiences during the 19th and early 20th centuries, the new Turkish republic’s foreign policy would be one of caution, independence and self-defense, characterized by a reluctance to meddle in foreign wars and a general orientation toward the West but without deep allegiance to a single power. As Timur Kuran, a Turkish-American professor of economics and political science at Duke University, put it to me recently, “The members of Mulkiye helped to restrain the state and helped to prevent politicians in power from using foreign policy for momentary gain.”

This entwining of the government and Mulkiye intellectuals explains why they have so often been persecuted. In 1960, students so vociferously protested the changes being made to the country by Adnan Menderes, Turkey’s leader at the time, that the university was temporarily shut down. Even as Mulkiye continued to serve its function as a feeder department to the Turkish state, university campuses like Mulkiye’s came to be seen as inspiration for greater, nationwide political opposition. Throughout the ’70s and ’80s, after two military coups, many leftist Mulkiye professors were purged and even thrown in jail. But even following these dramatic events, the very Mulkiye people who suffered would eventually go back to work for the government or return to teaching jobs. In 1971, for example, a Mulkiye dean named Mumtaz Soysal was accused of making Communist propaganda and sent to jail. “I heard he cleaned toilets in prison,” one former Mulkiye professor told me. Yet 20 years later, Soysal was Turkey’s foreign minister. Over time, several aspects of Mulkiye’s influence in the state bureaucracy were diminished, especially in the realm of local administration and finance. But even after so much trauma, Mulkiye — and particularly its prominence in foreign policy and the Turkish Foreign Ministry — survived.

In the 1980s, students like Ilhan Uzgel entered Mulkiye to work toward advanced degrees and stayed on as professors. By that time, a government-controlled institution called YOK, created to exert more centralized control over the universities, had been given purview over a suite of traditionally independent functions ranging from admissions testing to tenure decisions. The Mulkiye faculty split into right and left. The secularist-nationalists opposed some liberal reforms to the economy; they were critical of the Kurdish struggle and political Islam, and some were against joining the European Union. The leftists and liberals favored human rights (including for Kurds and Islamists), entry into the E.U. and broader democratization. In 1998, the Turkish military shut down the ruling Islamist political party and imposed further restrictions on political Islamists and other religious figures. Erdogan, then mayor of Istanbul, was sent to prison. By the 2000s, a more liberal-seeming, post-Islamist party led by Erdogan was ascendant. Many Mulkiye academics were so inclusive in their thinking as to have been sympathetic to Erdogan when he became prime minister in 2003.

Soon after, though, something began happening behind the scenes. “Mulkiye’s ties with Turkish bureaucracy began to be cut off around 2004,” Uzgel told me. “The A.K. Party just cut it off. Their own people began to dominate the bureaucracy system.”

“I grew up at Mulkiye,” Elcin Aktoprak was saying. “Inside the campus, there was a kind of freedom that didn’t exist in the rest of the country.” I met Aktoprak, Canberk Gurer and Kerem Altiparmak, all former Mulkiye academics, at their office at a European Union-funded human rights organization, which sits in a lovely central neighborhood in Ankara. They are in their 30s and 40s. Aktoprak has short, unfussy hair and the easy confidence of many female Turkish intellectuals. (She and Uzgel have divorced in the time since the purge.) She felt more comfortable at Mulkiye as a woman than in other parts of Turkey, as did many self-described feminists, gay students, Kurds and leftists.

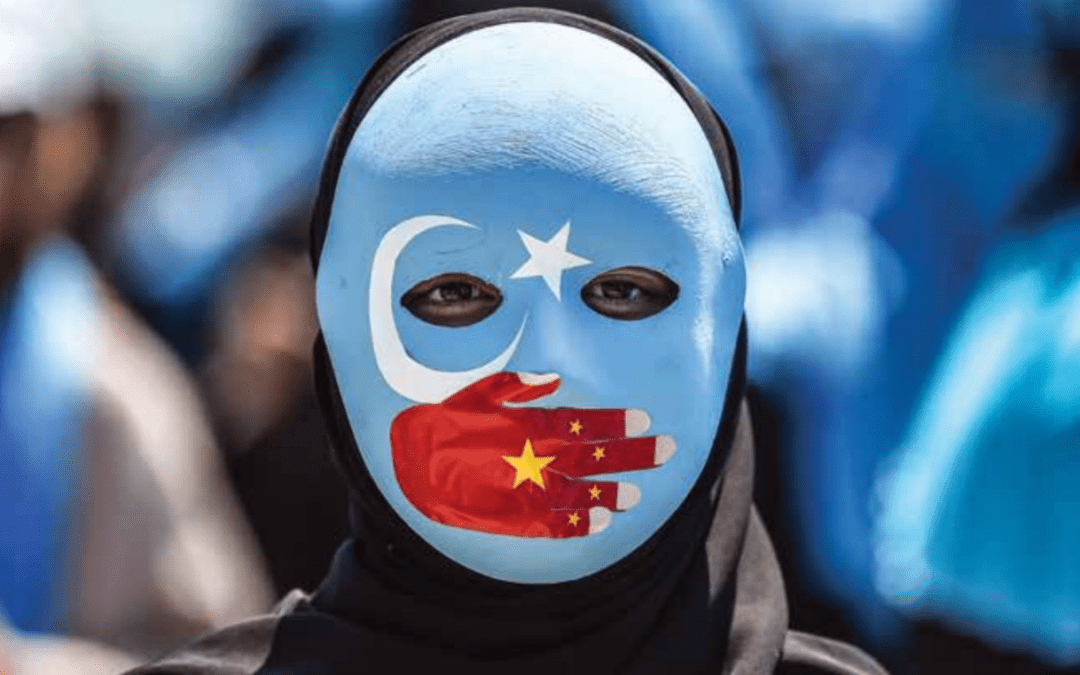

The Alliance is predicated on the idea more must be done to protect members of religious minority groups and combat discrimination and persecution based on religion or belief. The Alliance intends to advocate for freedom of religion or belief for all, which includes the right of individuals to hold any belief or none, to change religion or belief and to manifest religion or belief, either alone or in community with others, in worship, observance, practice and teaching. The Alliance is intended to bring together senior government representatives to discuss actions their nations can take together to promote respect for freedom of religion or belief and protect members of religious minority groups worldwide. Alliance members should be committed to the following principles and commitments and be willing to publicly and privately object to abuses, wherever they might occur.

The Alliance is predicated on the idea more must be done to protect members of religious minority groups and combat discrimination and persecution based on religion or belief. The Alliance intends to advocate for freedom of religion or belief for all, which includes the right of individuals to hold any belief or none, to change religion or belief and to manifest religion or belief, either alone or in community with others, in worship, observance, practice and teaching. The Alliance is intended to bring together senior government representatives to discuss actions their nations can take together to promote respect for freedom of religion or belief and protect members of religious minority groups worldwide. Alliance members should be committed to the following principles and commitments and be willing to publicly and privately object to abuses, wherever they might occur.